A DHT for iroh

by Rüdiger KlaehnDoes this work?

Ok, now it seems that we have written a rudimentary DHT. There are some missing parts, such as routing table maintenance. Every query will update the routing table by calling nodes_seen or nodes_dead, but we also want to actively maintain the routing table even if there are no user queries.

But before we get lost in these details... Does this thing even work? Sure, we can write unit tests for the various components such as the routing table. But that won't tell us all that much about the behaviour of a system of thousands of nodes.

What we need is a realistically sized DHT that we can just prod by storing values and see if it behaves correctly. Ideally we want to be able to do this without setting up a kubernetes cluster of actual machines. For the behaviour of the algorithm in the happy case it is sufficient to just simulate a lot of DHT nodes in memory in a single process, connected via irpc memory channels.

For a slightly more realistic simulation we can create a large number of actual DHT nodes that communicate via iroh connections. This can still all happen within a single process, but will be more expensive.

Taking a step back, what does it mean for a DHT to work anyway? Sure, we can put values in and get them out again. But there are various pathological cases where the DHT will seem to work but really does not.

E.g. the DHT could decide to store all values on one node, which works just fine but completely defeats the purpose of a DHT. Or it could only work for certain keys.

So we need to take a look at the DHT node internals and see if it works in the expected way.

Validating lookups

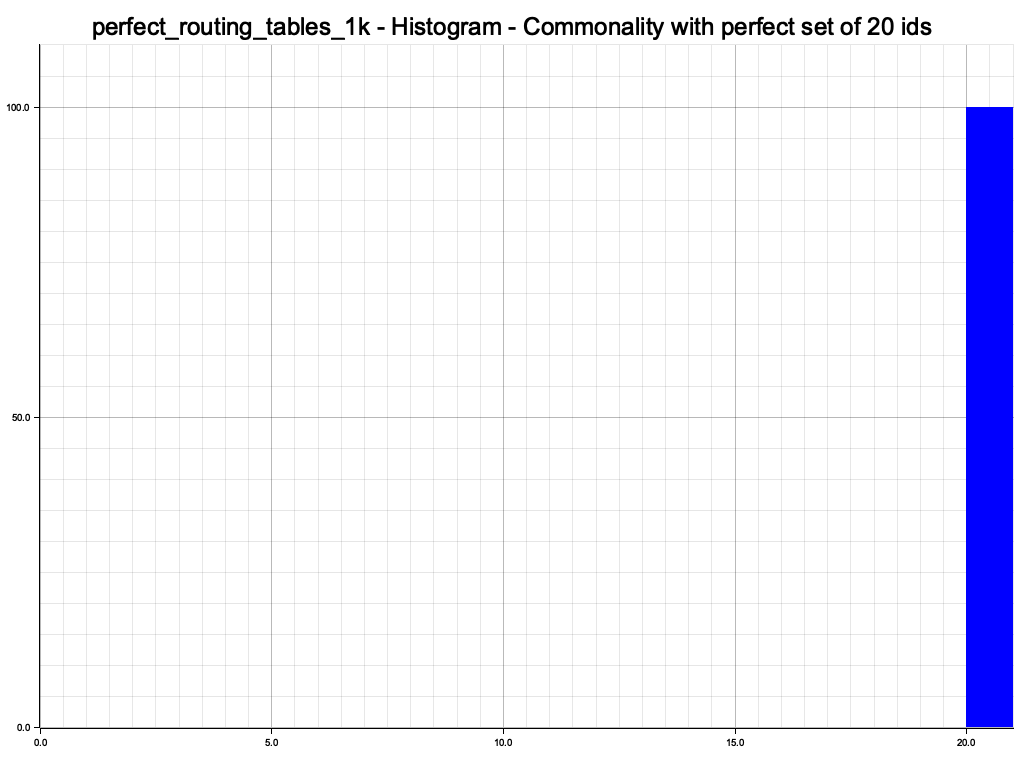

As we have seen, the iterative algorithm to find the k closest nodes is at the core of the DHT. Fortunately, for a test scenario we know the perfect result of that call. We can just take the entire set of node ids we have set up for the test, compute the k closest to the target node, and compare this set with the set returned by lookup/iterative_find_node. The intersection between the set returned by lookup and the perfect set of node ids gives us a somewhat more precise way to measure the quality of the routing algorithm. For a fully initialized DHT it should be almost always perfect overlap.

Almost, because the algorithm is random and greedy, and there is always a tiny chance that a node can not be found.

We need to perform this test for a large number of randomly chosen keys to prevent being fooled by a DHT that only works for certain values.

Validating data distribution

A perfect overlap with the perfect set does not mean that everything is perfect. E.g. we could have a bug in our metric that leads to always the 20 smallest nodes in the set being chosen. Both the brute force scan and the iterative lookup would always find these 20 nodes, but data would not be evenly distributed across the network, which defeats the whole purpose of a DHT.

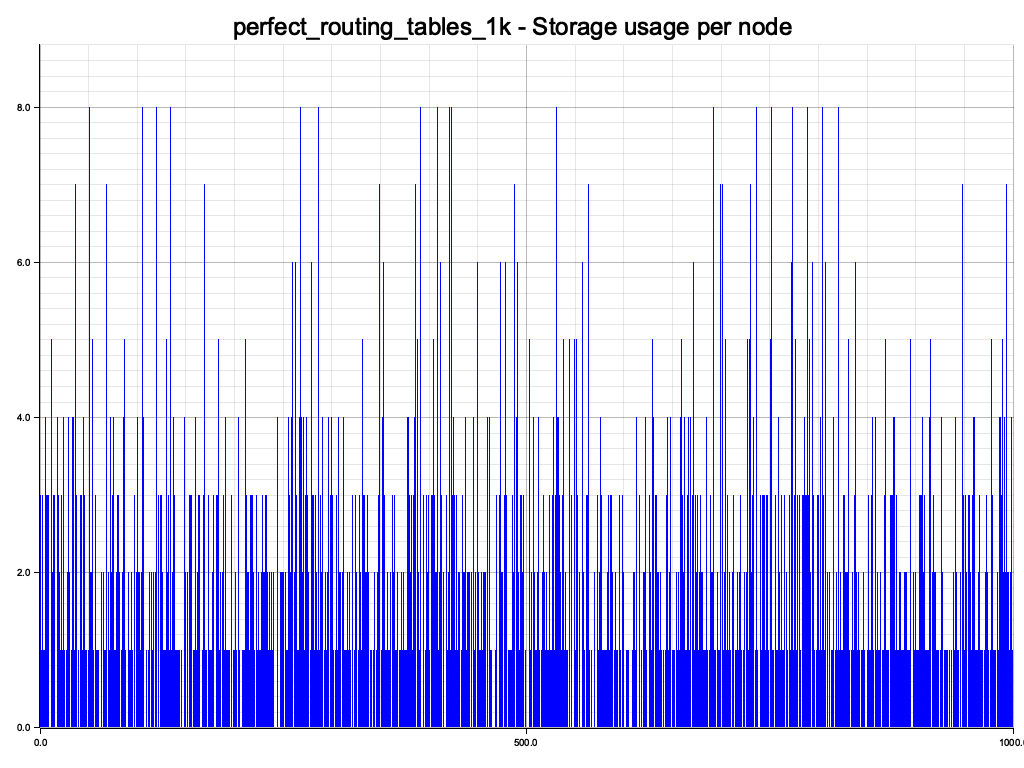

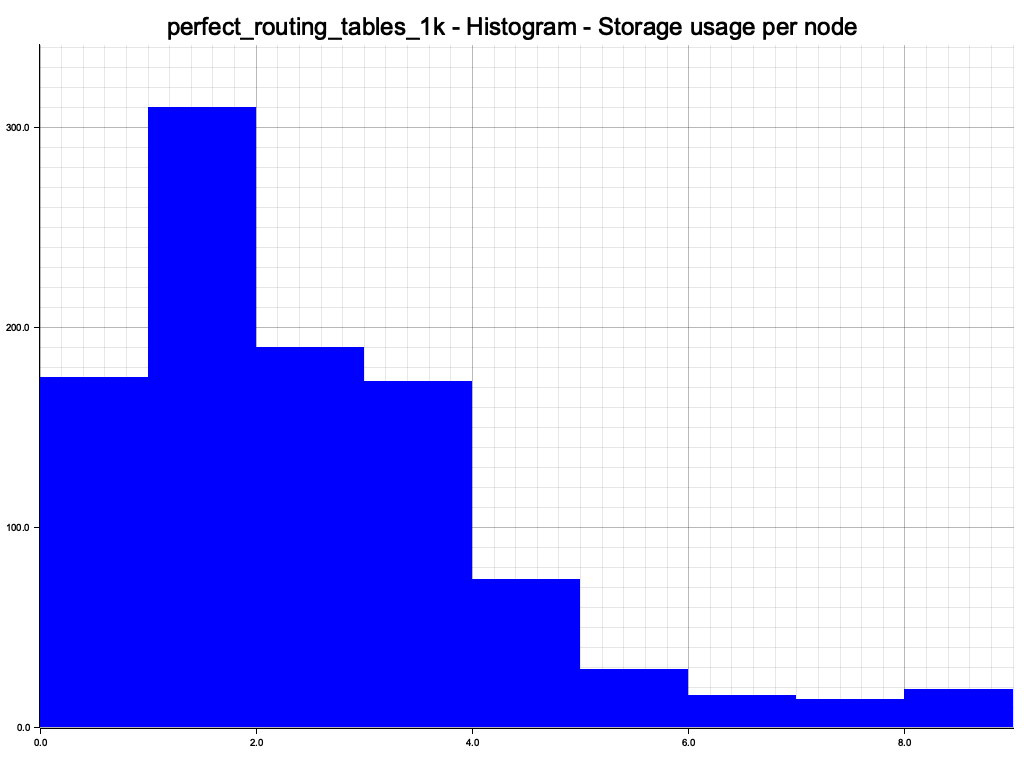

So another useful test is to store a number of random values and check the data distribution in the DHT. Data should be evenly distributed around all nodes, with just the inevitable statistical variation.

Visualizing the results

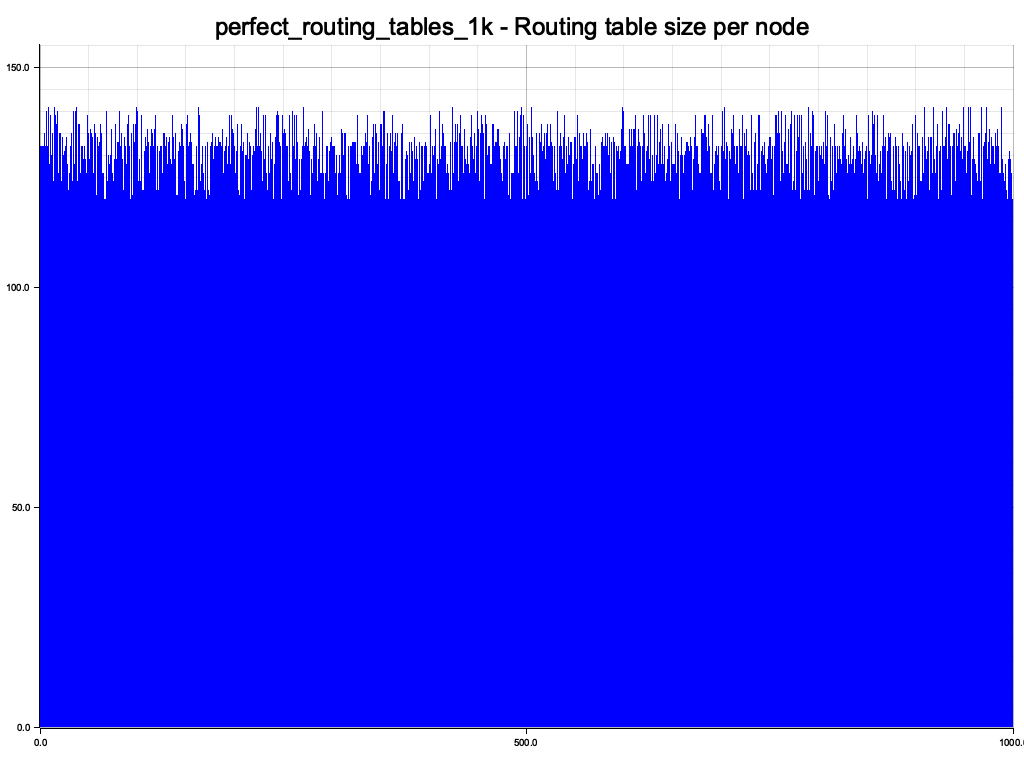

In all these cases, we are going to get a lot of data, and the results are not precise enough to be checked in classical unit tests. Instead we are going to plot things like overlap with the perfect set of node ids as well as data distribution, and to condense the information even further plot histograms of these distributions.

Later it would be valuable to compute statitical properties of the distributions and check them against expectations. But for now we just need some basic way to check if the thing works at all. So let's write some tests...

Testing in memory with irpc

One of the plumbing details we omitted when describing the inner workings of the DHT actor is the client pool. A DHT node is doing a lot of tiny interactions with a lot of nodes, so we don't want to open a connection every time we talk to a remote node. But we also don't want to keep connections open indefinitely, since there will be a lot of them. So one of the things the DHT actor has is an abstract client pool that can provide a client given a remote node id.

pub trait ClientPool: Send + Sync + Clone + Sized + 'static {

/// Our own node id

fn id(&self) -> NodeId;

/// Adds dialing info to a node id.

///

/// The default impl doesn't add anything.

fn node_addr(&self, node_id: NodeId) -> NodeAddr {

node_id.into()

}

/// Adds dialing info for a node id.

///

/// The default impl doesn't add anything.

fn add_node_addr(&self, _addr: NodeAddr) {}

/// Use the client to perform an operation.

///

/// You must not clone the client out of the closure. If you do, this client

/// can become unusable at any time!

fn client(&self, id: NodeId) -> impl Future<Output = Result<RpcClient, String>> + Send;

}

The client pool is used inside the DHT actor whenever it needs to talk to a remote client. It has ways to add and retrieve dialing information for node ids, but most importantly a way to get a RpcClient. This client can be backed either by an actual iroh connection, or just an extremely cheap tokio mpsc channel.

For testing, we are going to implement a TestPool that just holds a set of memory clients that is populated during test setup.

#[derive(Debug, Clone)]

struct TestPool {

clients: Arc<Mutex<BTreeMap<NodeId, RpcClient>>>,

node_id: NodeId,

}

impl ClientPool for TestPool {

async fn client(&self, id: NodeId) -> Result<RpcClient, String> {

let client = self

.clients

.lock()

.unwrap()

.get(&id)

.cloned()

.ok_or_else(|| format!("client not found: {}", id))?;

Ok(client)

}

fn id(&self) -> NodeId {

self.node_id

}

}

Each DHT node gets their own TestPool, but they all share the map from NodeId to RpcClient. So this is extremely cheap.

Tests with perfect routing tables

The first test we can perform is to give all nodes perfect1 knowledge about the network by just telling them about all other node ids, then perform storage and queries and look at statistics. If there is something fundamentally wrong with the routing algorithm we should see it here. At this point tests are just printing output, so they need to be run with --nocapture.

We are using the textplots crate to get nice plots in the console, with some of the plotting code written by claude.

> cargo test perfect_routing_tables_1k -- --nocapture

So far, so good. We get a 100% overlap with the perfect set of ids.

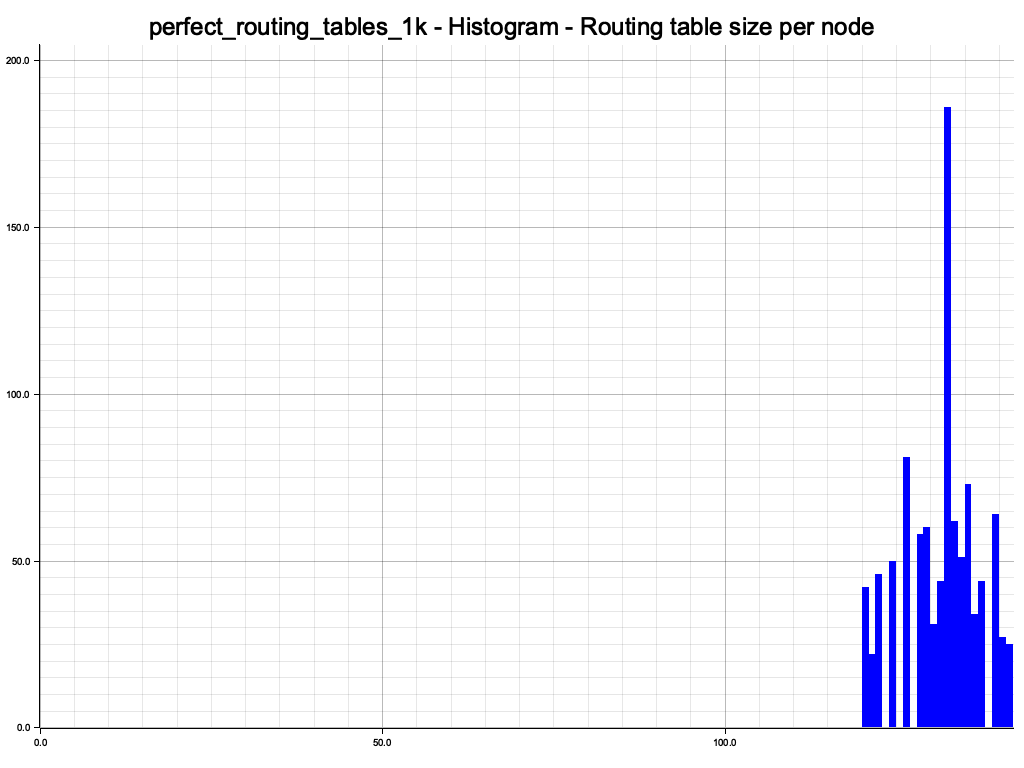

Data is evenly distributed over the DHT nodes. The histogram also looks reasonable. Since we have 100% overlap with the perfect set of nodes, the little bump at the end is just a blip, provided or XOR metric works.

All routing tables have roughly the same size. Not surprising since we have initialized them all with a randomized sequence of all node ids.

Tests with almost empty routing tables

But the above just tells us that the DHT works if we initialize the routing tables with all node ids. That is not how it works in the real world. Nodes come and go, and the DHT is supposed to learn about the network.

So let's write a test where we initially don't have perfect routing information.

We need to give each node at least some initial information about the rest of the network, so we arrange the nodes in a ring and give each node the next 20 nodes in the ring as initial nodes in their routing table (bootstrap nodes). We know that in principle every node is connected with every other node this way, but we also know that this is not going to lead to perfect routing.

So let's see how bad it is.

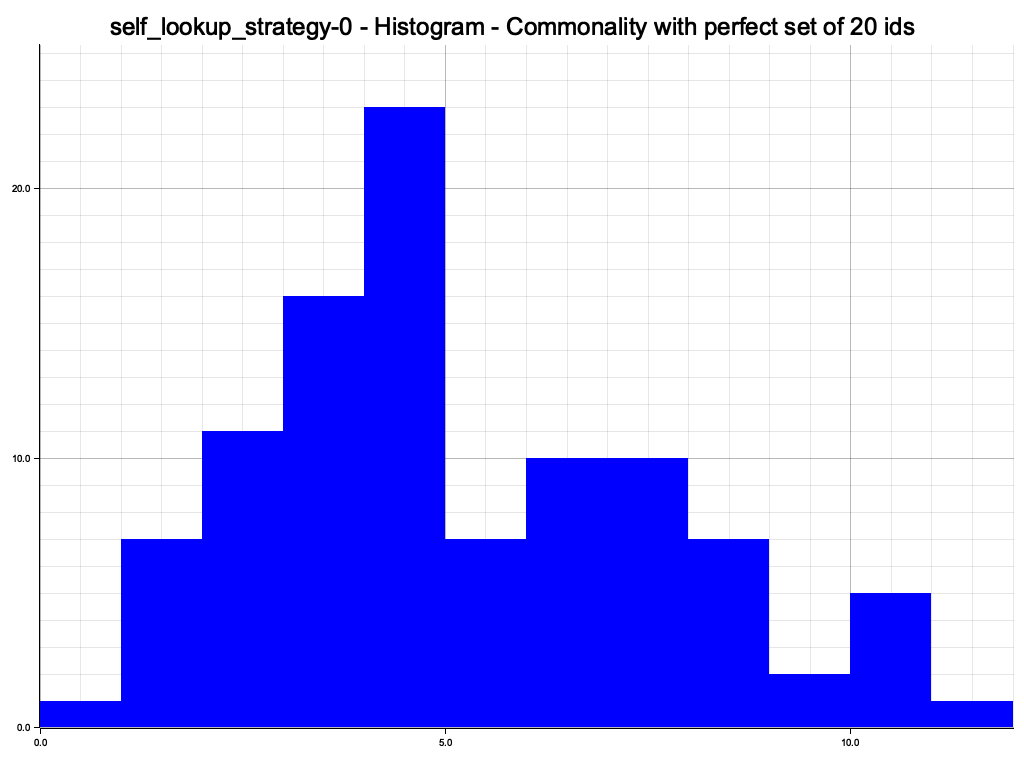

❯ cargo test just_bootstrap_1k -- --nocapture

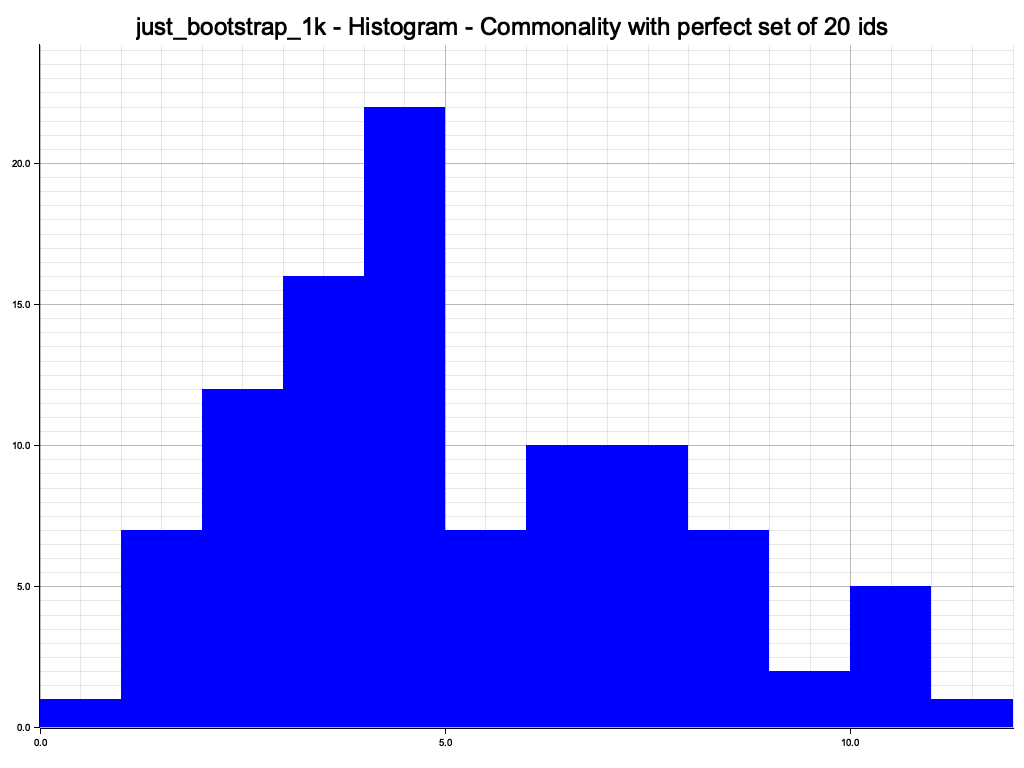

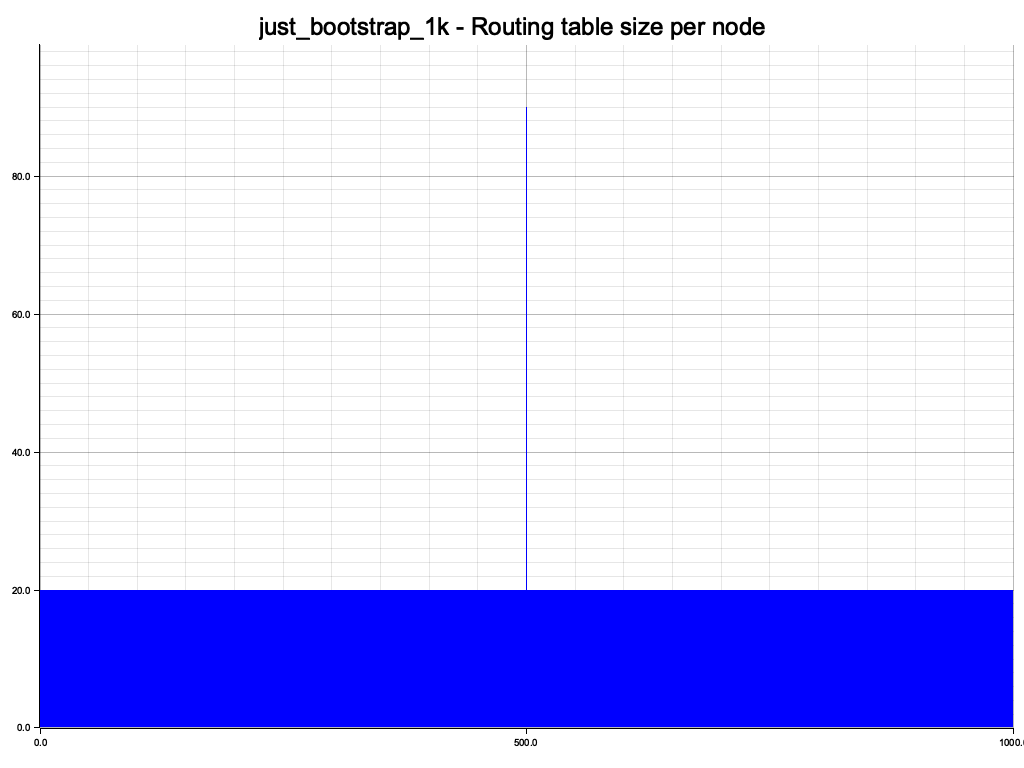

Pretty bad. The routing gives between 0 and 11 correct nodes. Note that even with this very suboptimal routing table setup the lookup would work 100% of the time if you use the same node for storage and retrieval, since it always gives the same wrong answer. If you were to use different nodes, there is still some decent chance of an overlap.

Let's look at more stats:

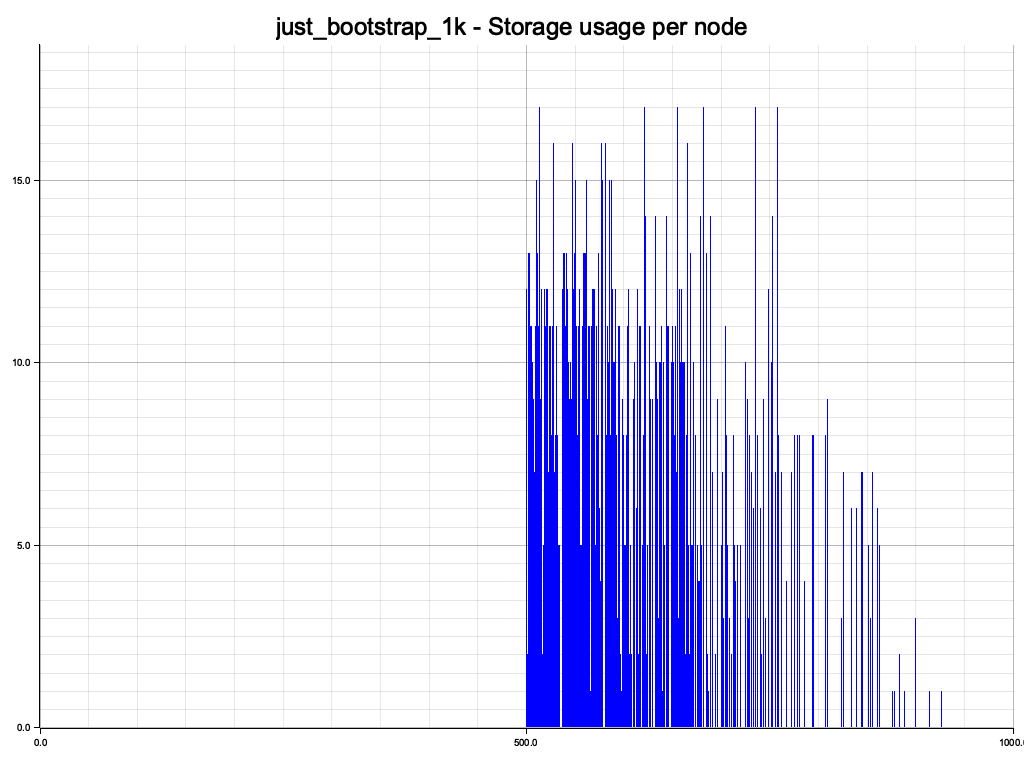

We interact with the node with index 500, and since each node only knows about nodes further right on the ring, the nodes to the left of our initial node are not used at all.

We have only interacted with node 500, so it has learned a bit about the network. But the other nodes only have the initial 20 bootstrap nodes. We have run all nodes in transient mode, so they don't learn about other nodes unless they actively perform a query, which in this case only node 500 has done.

Testing active routing table maintenance

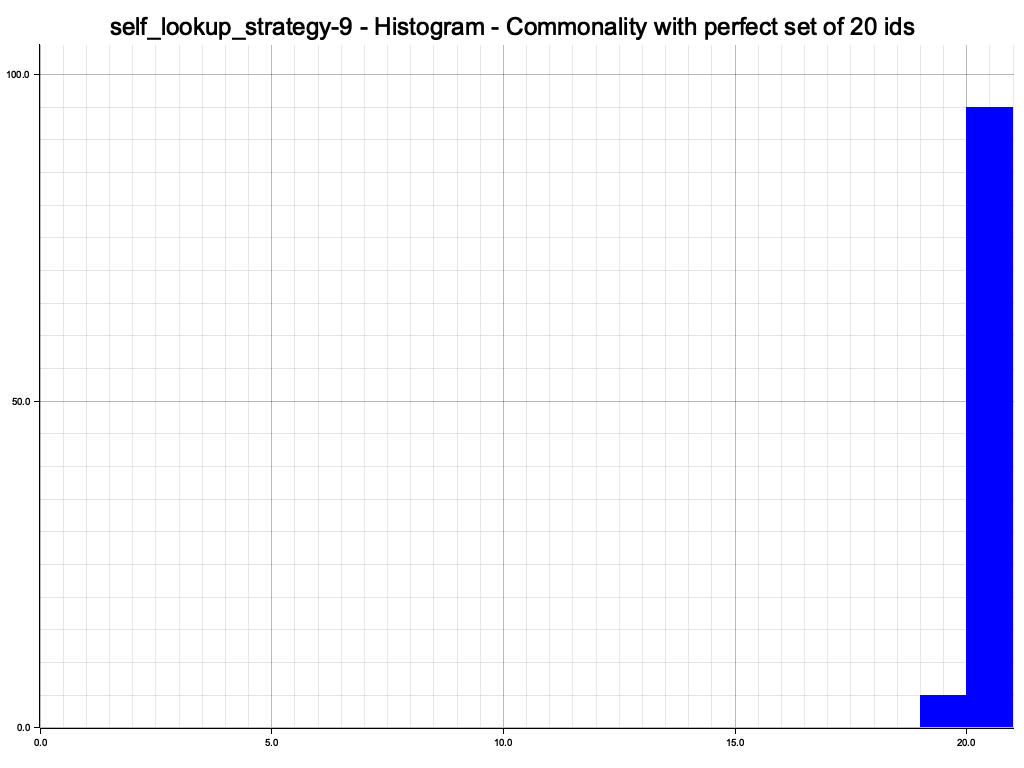

An important part of a DHT node is active routing table maintenance to learn about other nodes proactively. Here is a test where each node performs a lookup of its own node id in periodic intervals just to learn about the rest of the world.

cargo test --release self_lookup_strategy -- --nocapture

Initially things look just as bad as with just bootstrap nodes:

But after just a few random lookups, routing results are close to perfect for this small DHT

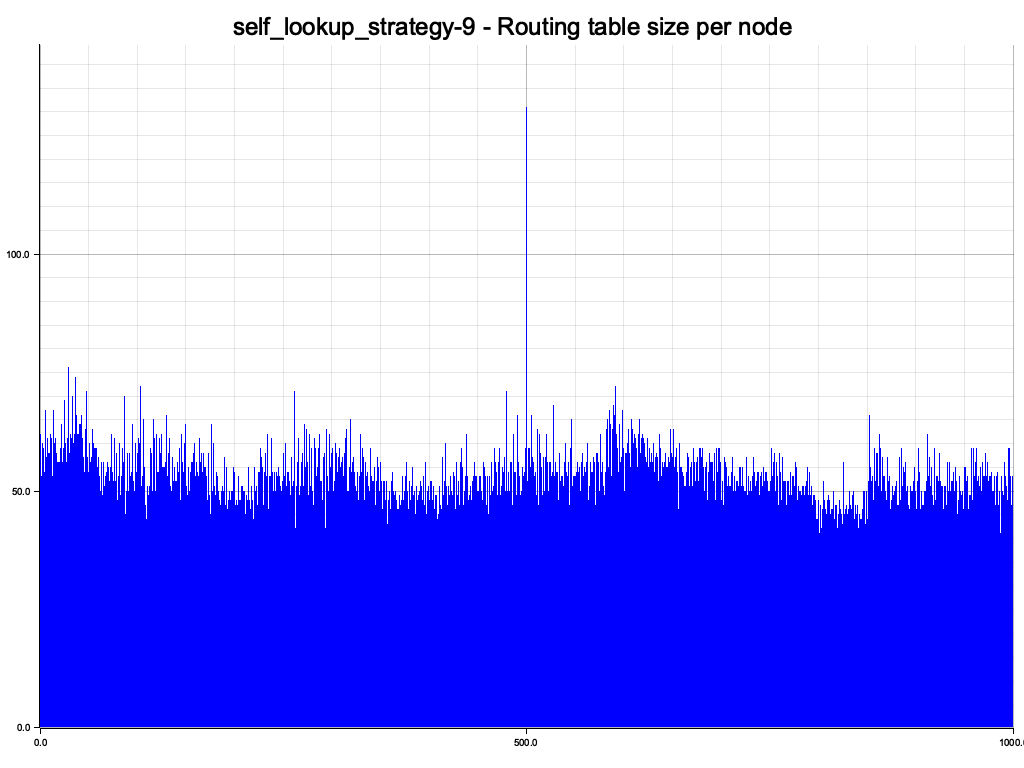

The node that is being probed can still be clearly seen, but after just a few self lookups at least all nodes have reasonably sized routing tables:

How big can you go?

With the memory based tests you can easily go up to 10k nodes, and even go up to 100k nodes with a lot of patience, on a 32GiB macbook pro. The limiting factor is the fixed size of the routing table. For a 100k node test, just the routing tables alone are ~20 GiB. You could optimize this even further by having a more compact routing table or my memoizing/Arc-ing node ids, but this would come with downsides for performance in production, and in any case 100k nodes already is a lot.

An evolving network

So now we have tests to show that the routing works as designed when the routing tables are properly initialized, and also tests that the routing table maintenance strategies work to properly initiailze the routing tables over time.

What is missing is to simulate a more dynamic network where nodes come and go. We need to know if routing tables eventually learn about new nodes and forget about dead nodes. These kinds of tests don't benefit from running over real iroh connections, so we are going to use mem connections.

Nodes joining

Having a static test setup with a fixed number of nodes is nice and simple. So we have to set things up such that we still have n nodes, but some are initially disconnected. Then do something to connect them to the rest and watch the system evolve. The key for this is the set of bootstrap nodes. We can set up some nodes without bootstrap nodes, and make sure the set of bootstrap nodes for the connected nodes does not contain any of the partitioned nodes. The partitioned nodes will be completely invisible from the connected nodes, as if they don't exist at all.

Then, after some time, do something to connect the disconnected nodes, e.g. tell each of them about one node in the connected set. That should be enough for them to eventually learn about the other nodes, and also for the other nodes to learn about them.

Let's look at the test setup:

async fn partition_1k() -> TestResult<()> {

// all nodes have all the strategies enabled

let config = Config::full();

let n = 1000;

let k = 900;

let bootstrap = |i| {

if i < k {

// nodes below k form a ring

(1..=20).map(|j| (i + j) % k).collect::<Vec<_>>()

} else {

// nodes above k don't have bootstrap peers

vec![]

}

};

let secrets = create_secrets(0, n);

let ids = create_node_ids(&secrets);

let (nodes, _clients) = create_nodes_and_clients(&ids, bootstrap, config).await;

...

}

We configure the nodes with all routing table maintenance strategies enabled. Then we create 900 nodes that are connected in a ring, and 100 nodes that don't have any bootstrap nodes (create_nodes_and_clients takes a function that gives the indices of the bootstrap node for each node).

Then we let the system run for some time so the 900 connected nodes have some time to learn about each other. Then comes the interesting part - we tell each of the 100 disconnected nodes about 1 of the 900 connected nodes.

for _i in 0..10 {

tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

// visualize results

}

let id0 = nodes[0].0;

// tell the partitioned nodes about id0

for i in k..n {

let (_, (_, api)) = &nodes[i];

api.nodes_seen(&[id0]).await.ok();

}

for _i in 0..30 {

tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

// visualize results

}

Now the 100 previously disconnected nodes should learn about the main swarm of 900 nodes, and more importantly the 900 nodes of the main swarm should learn about the 100 new nodes.

But how do we visualize results? First of all we need a way to show the state of the system at one point in time. We got 1000 nodes, so each node can have at most 1000 entries in its routing table. So we could have a bitmap of 1000 rows where each row is the routing table of that node.

But now we need to additionally show evolution of this bitmap over time. Fortunately there are great libraries for animated gifs in rust, so we can just generate an animated gif that shows the evolution of the connectivity map over time.

Here it is:

The big diagonal bar is the bootstrap nodes. As you can see they wrap around at 900. The lowest 100 rows are the routing tables of the initially disconnected nodes, and the rightmost 100 pixels is the knowledge of the connected nodes of the initially disconnected rows. Both are initially empty. As soon as the 100 partitioned nodes are connected, the 100 new nodes very quickly learn about the main swarm, and the main swarm somewhat more slowly learns about the 100 new nodes. So everything works as designed.

You could now experiment with different routing table maintenance strategies to make things faster. But fundamentally, things work already. After some time the 100 new nodes would be fully integrated into the swarm.

Nodes leaving

Another thing we need to test is nodes leaving. When nodes leave for whatever reason, the remaining nodes should notice and purge these nodes from their routing tables after some time. This is necessary for the DHT to continue functioning - a routing table full of dead nodes is worthless. We don't want to immediately forget about nodes when they are briefly unreachable - they might come back, but we should eventually get rid of them.

The way deleting dead nodes works in this DHT impl is also via random key lookups. If you notice during a key lookup that a node in your routing table is unreachable, you will purge it from the routing table briefly afterwards. So a node that has all the active routing table maintenance strategies enabled should also automatically get rid of dead nodes over time.

How do we test this? We have 1000 fully connected nodes like in many previous tests, then "kill" the last 100 of them and observe the evolution of the system. For our mem connection pool this is easy to do by just reaching into the underlying BTreeMap<NodeId, RpcClient> and removing the last 100 clients.

Here is the test code. We let the DHT connect for 10 seconds, then kill the last 100 nodes, and see how things evolve in the remaining 900 nodes for some time.

async fn remove_1k() -> TestResult<()> {

let n = 1000;

let k = 900;

let secrets = create_secrets(seed, n);

let ids = create_node_ids(&secrets);

// all nodes have all the strategies enabled

let config = Config::full();

let (nodes, clients) = create_nodes_and_clients(&ids, next_n(20), config).await;

for _i in 0..10 {

tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

// write bitmap

}

for i in k..n {

clients.lock().unwrap().remove(&ids[i]);

}

for _i in 0..40 {

tokio::time::sleep(Duration::from_secs(1)).await;

// write bitmap

}

// write animated gif

Ok(())

}

And here is the resulting gif:

You can clearly see all nodes quickly forgetting about the dead nodes (last 100 pixels in each row). So removal of dead nodes works in principle. You could of course accelerate this by explicitly pinging all routing table entries in regular intervals, but that would be costly, and only gradually forgetting about dead nodes might even have some advantages - there is a grace period where nodes could come back.

What's next?

So now we got a DHT impl and have some reasonable condidence that it works in principle. But all tests use memory connections, which is of course not what is going to be used in production.

The next step is to write tests using actual iroh connections. We will have to deal with real world issues like talking to many nodes without having too many connections open at the same time. And we will move closer to a DHT implementation that can be useful in the messy real world.

Footnotes

-

The nodes will not retain perfect knowledge due to the k-buckets being limited in size ↩

To get started, take a look at our docs, dive directly into the code, or chat with us in our discord channel.